Understanding Multiwire Branch Circuits in Home Electrical Systems

Multiwire branch circuits are an uncommon but intriguing wiring technique in home electrical systems. To the untrained eye, a panel wired with this technique may look typical, but a knowledgeable inspector should be able to spot and explain the key differences.

Setting the Stage: Key Electrical Concepts

Before diving into multiwire branch circuits, let’s review some basics:

Conductor, Wire, and Cable

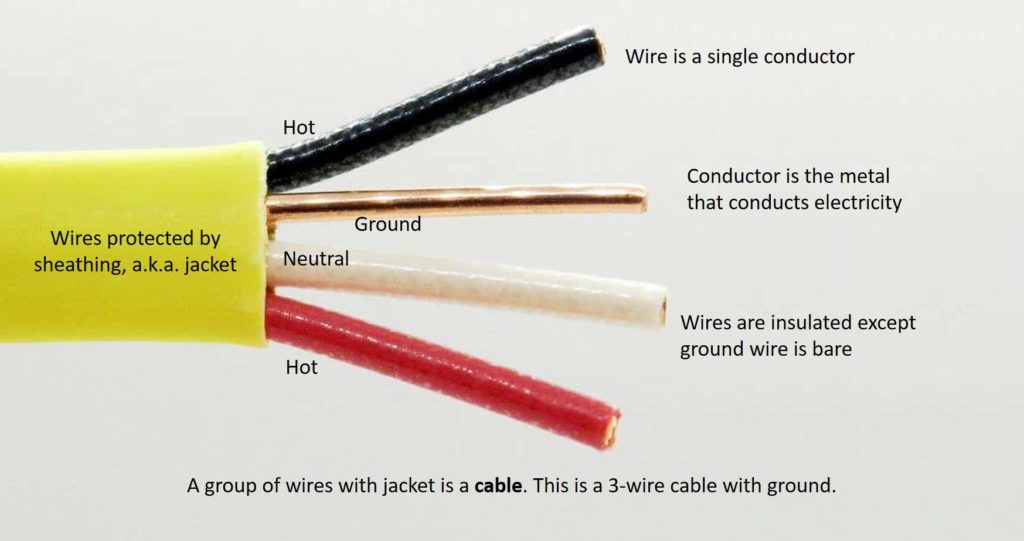

- Conductor: The metal (usually copper or aluminum) that carries electricity.

- Wire: A conductor that may be bare or covered with a plastic insulator.

- Cable: Two or more wires bundled together in a protective sheathing or jacket.

In most homes, electrical systems use single-strand insulated copper wires bundled into 2-, 3-, or 4-wire cables. For this discussion, we’ll focus on the use of 3-wire cables.

Typical Uses of 3-Wire Cables

However, there’s a non-typical use of 3-wire cables that is the focus of this article: Multiwire Branch Circuits (MWBCs).

What Are Multiwire Branch Circuits (MWBCs)?

A multiwire branch circuit, sometimes called a shared neutral circuit, is a unique way to use a 3-wire cable. According to the National Electric Code (NEC), it’s defined as:

“A single electrical cable with two circuits that have a voltage between them and share a common neutral.”

From this definition, two key features emerge:

- Two Circuits in One Cable

- Unlike conventional use where one cable serves one circuit, MWBCs allow a single cable to serve two circuits.

- For example, the black wire might power the living room, while the red wire powers the dining room. Both circuits share the same neutral wire but are on separate breakers.

- Opposite Phases in the Panel

- The two circuits must terminate on separate phases in the panel to reduce the current flow on the shared neutral wire.

- The two circuits must terminate on separate phases in the panel to reduce the current flow on the shared neutral wire.

Advantages of Multiwire Branch Circuits

- Reduced Cable Use

- A single 3-wire cable replaces two 2-wire cables, reducing clutter and simplifying the panel’s wiring.

- Space Savings in the Panel

- Fewer cables entering the panel mean fewer connections, leading to a cleaner and more organized panel.

Disadvantages and Potential Risks

- Neutral Overload

- The two hot conductors must connect to opposite phases. If circuits are moved around during modifications and both end up on the same phase, the neutral conductor can become overloaded.

- Neutral Disconnection Risk

- If the shared neutral wire is disconnected, it can create a dangerous condition with varying voltages on the two circuits, potentially damaging equipment. The Electrical Code Academy explains how it happens: Understanding the Dangers of Multiwire Branch Circuits.

- Breaker Dependency

- De-energizing the entire cable requires turning off two breakers.

- Increased Complexity

- This method adds complexity and risk for minimal wiring savings, especially if improperly maintained or altered.

What Should You Do if Your Home Has MWBCs?

If your home or prospective home features MWBCs, there’s no need to panic. However:

- Ensure that any modifications or repairs are carried out by a certified electrician.

- If you’re purchasing the home, consider having a licensed electrician inspect and certify that the wiring is correct.

By understanding MWBCs, you’ll be better prepared to identify, maintain, and safely manage this uncommon yet practical wiring technique.

A core principle at Chester County Home Inspections is that we educate our clients, whether verbally at the inspection, through our detailed reports, or through specialty articles like this. Schedule online now, or inquire online, or call or text (484) 212-1600.